Full disclosure: I do not get a hashtag tattooed to my face in this speech.

Second full disclosure: there's no video.

I know, I know. It's both a shame and a relief.

It's a shame because the Q&A actually ran longer than the speech itself, and people asked some amazing questions, including how I use technology as a writer and whether a man who likes every picture on a woman's profile is trying to "mark his territory." Alas, those moments are lost to history.

It's a relief (to me) because my 5th grade Latin teacher just happened to introduce me. She tapped my best friend from high school for some material and he spilled every embarrassing story he could remember, including ones that involved nudity and a certain bronze bull in winter. Thus evaporated any chance I had of looking intelligent in front of language and literature grad students and professors. Sigh.

Anyway, the speech turned out pretty all right, so I thought I'd share it.

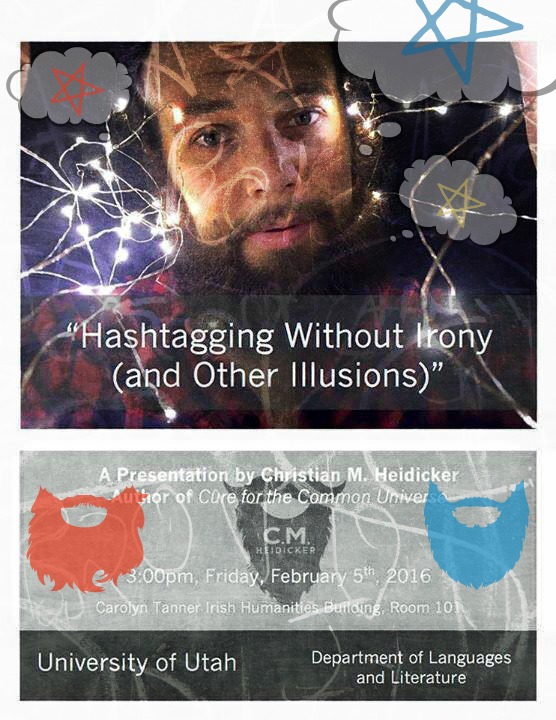

Molly Barnewitz, comic book afficienada, invited me to speak at her conference titled Confutati (or #Culture), which aimed to trace the impact of our ever changing media and its effect on contemporary discourse and self-representation.

(Fear not. I don't use words that big in the actual talk.)

Here's the speech. I know, lotsa text without much space. Yuck. Fortunately, I love you, so I broke it up with some totally unrelated, increasingly interesting, copyright-free pictures!

Yer welcome.

HASHTAGGING WITHOUT IRONY

(and Other Illusions)

Before I was asked to speak at this conference, I didn’t give a damn about hashtags. Now I think I may care about them a little. I’ll tell you why.

I started researching this speech in the most boring, writerly way possible. I Googled hashtags. I’ll spare you the history of the pound sign that preceded it, although if you’re into pure, unabashed geekery, I highly recommend you watch Hank Green’s video on the Octothorpe.

The history of the hashtag itself is pretty straightforward.

On August 23rd, 2007, a man named Chris Messina, who hilariously trademarked his name for some reason, tweeted a suggestion that the pound sign be used before groups as a way to narrow search results. This, he argued, would be far more efficient than firing a single tweet into the vast internet conversational war zone, hoping the message would reach its intended audience. One of Twitter’s founders, Evan Williams, responded to this tweet, saying it was too technical to catch on. (I guess he didn’t have faith in users being able to press the shift key and the number 3 at the same time.)

But then, of course, the hashtag’s use spread like wildfire . . . after it was used to report on the San Diego wildfire, naturally.

As with all new inventions, feelings about the hashtag were mixed. On one end of the spectrum, the hashtag became a hip new way of socializing (i.e. “I just got some froyo #yum #froyo #bestdayofmylife”). On the other end of the spectrum the hashtag was perceived as yet another juvenile trend from the internet age that dulled the sharpness of our ability to communicate (#froyo).

Of course, like so many trends after they’re first introduced (comic books, movies, novels), what appeared like the degradation of culture had inherent value. The hashtag was nothing more than an efficient filing system for an increasingly messy communications arena. Hip trendsetters were merely insistent cataloguers, organizing a sliver of the supernova of new information, allowing users to access exactly what they desired. A person could search #hoverboard and save their child a cracked skull on Christmas morning.

The hashtag isn’t cultural erosion. It’s a librarian’s wet dream.

But that isn’t how it’s perceived most of the time, is it?

When finding a title for this speech, Molly and I had to be careful not to elicit too many eye rolls from the department. When I told a friend I was researching hashtags, without missing a beat, he said, “They’re for idiots.”

And he didn’t just mean kids.

It was only a matter of time before the older end of the internet spectrum adopted and started abusing the hashtag. One hip mom in her forties who wanted nothing more than to be like her teenage daughter (I’m sure you’re all friends with this woman on Facebook) started to spread the hashtag around her age group, and it quickly became passé amongst the young, because now old people sounded just as stupid using hashtags as they, the young, once had.

I recently watched a puff piece where an interviewer asked Jon Stewart if he was “hashtag happy.” She wasn’t asking if he overused hashtags. She wasn’t asking if the work on his wife’s animal farm was something he wanted to file away in the Department of Records for all time. She was trying to connect with her audience in their forties and fifties, who were just catching on (wrongly) with how hashtags are used.

There was a brief window in there (and I’m not convinced it’s over) where just using a hashtag could make you appear at once incompetent to anyone over the age of twenty-six and desperate for attention to anyone under the age of twenty-five. And so our incredibly awesome new filing system was wedged into the comfortable space of irony, ensuring that the most mundane actions and acts of painful self-awareness would be filed away in the Department of Records in burgeoning terabytes of meaninglessness.

(As of January 29th, #ihatehashtags has 87,400 results on Google.)

But this isn’t a speech on the cultural history or significance of the hashtag. This is a speech about the tools we have available to us as writers and communicators and just how slippery they can become. In just five years, an excellent filing system can shift from super efficient to super trendy to super lame to super ironic. It’s how most things work these days, for better or worse, and unfortunately, how we’re perceived when using a tool dictates how we end up using them.

WHY WE NEED THEM

So how do we use them? Wait, no, that’s a stupid question. We all know how most people use hashtags, and that is poorly. The real question, I suppose, is how should we use them? To create groups as a means to narrow our audience? Sure. But certainly they can serve a nobler purpose. We should (and occasionally do) use hashtags to inform people with lots of money and a public platform exactly how we feel about stuff.

Forget Nielsen. Forget polling. We’ve got hashtags.

And we need them. When it comes to people in power, there’s a whole lot of guesswork involved in how people spend their days, and it’s only briefly illuminated by voluntary box checkers or how many additional cans of Coke sell after a Superbowl ad airs. You’d think the measurements would be more exact in 2016, but they aren’t.

In case you’re unaware, the Nielsen Ratings are a measuring system that was created to determine how many people tune in to a specific television program at a given time so that networks can know how much to charge for commercials during that time slot and whether or not to keep the show on the air.

If you’re anything like I was before looking into this, you might be wondering if in this internet age, companies like NBC or Netflix can’t just look at their fancy network computers and see who’s watching what. The answer is, they can’t. That would involve collecting our personal data, and they can’t legally do that.

In steps Nielsen.

These measurements are far from perfect. When they first started out, Nielsen traveled from home to home asking average Joes and Joanns and Jo-x’s what they watched and then used a rough metric to approximate the audience size. Today, they select 5,000 households that they feel fully represents the 99 million people in America who actually own TVs and then install meters on their televisions to track what they’re watching. In other words, because I haven’t given Netflix express permission to track my data, I don’t have to worry about some executive giggling about the fact that while I was supposed to be working on this speech, I watched seventeen straight episodes of Gilmore Girls.

That’s a joke.

Maybe.

The point is there’s no way for you to find out.

This measuring system is how popular shows like Arrested Development and Firefly get canceled while American Idol ran into its fifteenth season. The Nielsen folks ask the wrong people what they were watching.

Enter the hashtag.

The Nielsen Ratings just announced, five days ago, that they were going to start using hashtags in their calculations of what people are watching. Obviously, they’re a little behind, like a great-aunt who makes a last-ditch effort to connect with you before she dies and buys you a first generation iPod.

For years, we’ve all known what they’re just catching onto. In the Neverland of the internet, everything is a little Tinkerbell that needs clicks instead of claps to stay alive. The hashtag is like a disposable wand that directs a message to the eight corners of the internet, trying to make us all believe in one thing.

Enough people use #froyo in a single day and it’s almost guaranteed that Hillary Clinton and Ted Cruz will be paying a visit to a froyo shop for a photo op. (Mike Huckabee will be there too, but not because he’s running anymore or knows anything about the internet; he just loves food analogies. Make up your own Bernie Sanders/free samples joke here.)

It’s interesting to think that we are in the rather unique modern position of having politicians listen to us directly for once, because they no longer have to guess at what everyone’s talking about.

I hate to say it, but presidential polls are even more inaccurate than the Nielsen Ratings when it comes to taking the country’s political temperature. Until recently, I was also ignorant as to how all this works, so I’m going to assume you’re all in the dark as well and quickly break polling down for you. Yes!

Pollsters obviously can’t ask people’s televisions how they’re voting, although I’m sure they could gather a few clues depending on what news organizations a household tunes into. No, instead pollsters must hand dial a list of citizens who have volunteered their phone numbers and then ask them how they’re planning to vote. Here’s the crazy thing: because of privacy laws, they’re only allowed to call landlines—phones that have to be plugged into a wall to function.

2016. Landlines.

As you might imagine, the only people around with landlines are older. This demographic is narrowed further still when the sweetest old people hang up on the pollsters the second they realize they aren’t speaking to their grandchild. This is why people who were sweating the polls and fearing a Trump presidency could breathe a little easier this week. Polls are unreliable, unless you’re trying to get people to rally around a candidate they otherwise wouldn’t believe could win.

Unlike polls or Nielsen ratings, the hashtag is like a ninja star straight to the heart of politics. All politicians watch the news. And the news, fortunately for us, acts a lot like that “hip” forty-year-old mom who wants to be like her teenage daughter. News people pay attention to hashtags because they are trendy. This means hashtagging about your favorite show or your favorite candidate can actually make a difference so long as others hashtag about it too.

So the good news is we’ve got a wonderfully effective tool on our hands.

The bad news is we aren’t wielding it very well.

MAGICK

So why have I, a 33-year-old man, who’s straddling the fence of youth and the elderly, become so interested in the hashtag all of a sudden? In order to answer that question, I have to abandon technology completely, and talk about its polar opposite—magick. And no I don’t mean the staged illusions of David Blane or Chris Angel. I mean Magick, spelled with a ‘k,’ moonlight and madness, babe of the abyss, give Mother a heart attack, Alan Moore’s got your soul in his beard, Magick.

I’ve actually been on a bit of a quest for the past couple years to find a universal definition of Magick and fortunately I have so far been unsuccessful. Once I find this definition, I will wither up and die. (I just decided that. Maybe it will come true.)

Among the many definitions for magick, I have found the following:

- Arthur C. Clarke’s ‘Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.’ (Meh. I think we all got over that with the sixth iteration of the iPhone)

- Magic is the work of the subconscious. (too Freudian)

- Magic is art or an extended fiction. (too obvious)

- Magic is a disease of language. (we’ll come back to that)

- And finally, from the dictionary: ‘Magic is the power of apparently influencing the course of events by using mysterious or supernatural forces.’

Let’s work with this last one. I’m just going to assume you all already know that magick is inherent in everything we do, especially as writers. The verb to spell (as in C-A-T) was derived from casting a spell. Spelling something correctly will make your spell more effective. Also, studying your grammar—derived from the word grimoire, a book of magic—can make a lot more people pay attention to you on Facebook.

We are all casting spells on each other—constantly. I’m casting a spell on you right now by using my larynx to vibrate the air with commonly understood letter combinations in order to make things come to life inside of your head. (#librarianswetdream) This type of magick isn’t restricted to the auditory realm, of course. A few pixels on your phone can make your stomach flutter or plummet. The right hashtag at the right time can make you donate your last ten dollars to a cause. There is no physical contact in these situations. No one’s stabbing or embracing you. We are all transformed by lights and vibrating air.

This process has become less mysterious in our modern age as we come to learn about how the human brain functions, but it’s still fairly amazing that our proverbial tongues are connected to each other’s proverbial heartstrings. Unfortunately, it’s all become so commonplace in our daily lives that we don’t think of it as special anymore.

A big part of that must derive from a feeling of helplessness. We’re all aware that we’re able to cast large spells by combining our collective desires or outrages into a digital tidal wave of feeling so big that people with money and power transform how they behave.

The problem is that our signal is almost always lost in the noise.

DARK MAGICK

There are dark and light sides to all magick, even hashtag magick, and I do not say that ironically.

There are organizations today that can cast much bigger spells than everyone on this campus combined. They’re called advertisers. They are the most powerful magicians of our time, and that, I’d like to go on record as saying, is bullshit. (Thanks, Cindy.) With a wave of their bank accounts, they can make everyone in the country think the exact same thing at the exact same time and make it stick.

If you need a test of just how effective this magic is, try this. Sit down and write a list of every important historical woman you can think of. Next to it write a list of every commercial jingle you can remember. Which list is longer? (I’m not saying Rosalind Franklin is more important than Tasting the Rainbow—oh wait, yes I am saying that.)

Naturally, advertisers adore hashtags, not only for their trendy values but for their ability to measure potential customers. Our lovely library filing system is mostly being used to sell cars and toilet paper and fried chicken and emasculating energy drinks. The dark side of hashtag magic is making us jigglier and less satisfied and greedier and all the bad things you read about in fairy tales.

LIGHT MAGIC

So what is the light side?

We all know the hashtag can achieve much loftier goals than advertising. With #activism it can be used as a little awareness machine. It can make #Kony2012 the greatest super villain on Earth or #bringbackourgirls play on the lips of dozens of celebrities or #icebucketchallenge the absolute apex of advertising and noble causes and irony. And this a good thing. By merely being on the internet, we’re all granted the same healing magic as the dark magic of the advertisers. Collectively, we can fill the internet with important things. We can make more hearts beat for Alan Kurdi, the drowned Syrian three-year-old. We can do the news’s job and point out how many black people are murdered by police officers every month. We can—ahem—generate awareness and have money funneled toward these issues and try to combat injustice.

So. Light and dark. It’s pretty obvious what to do, right? Just use hashtags for light magic. Dump a bucket of ice water on your head and attach that little eight-pointed wand, and it will tug on the many heartstrings of the internet and this will cure ALS.

Simple, right?

NO WONDER WE’RE IRONIC

Well, of course not. Nothing can be that simple.

Not only do we run the risk of sounding like idiots when we use hashtags, but even when we find a solid reason to use them, #bringbackourgirls for example, we eventually have to sober up to a pretty devastating realization: our well-meaning hashtags don’t do much.

Hashtags in the end are nothing more than illusory magic, just like a David Blane special. It’s a big fireworks show, and those fireworks have only one message: WE CARE. We care that your daughters and sisters were abducted. We care that your children are drowning. We care that there’s a man who seems solely responsible for the enslavement and rape of young people in the Congo.

I hate to bum you out, but those girls were never returned, the Syrian refugees have yet to be accepted into our country, and KONY, if he is the villain that video made him out to be, is still at large. What’s even worse is when we start to learn the nuances of a situation that couldn’t be captured in 120 characters.

There’s a reason we never saw:

#KONY2012WATCHOUTTHISCREATORISAPUBLICMASTURBATOR

or

#icebucketchallengeyourfriendstodumpwaterontheirheadswithoutellingthemwhytheyredoingitorthatmostoftheproceedswillgotoourceo

or

#bringbackourgirlsunlessittakesmorethanacoupleofweeksinwhichcaseAmericanswillprobablyforgetallaboutitandyoucanjustkeepem

The only tangible effect was that for a short time we got to feel real, real good about ourselves. This type of magick is dangerously effective. In the fairy tales, it’s called a glamour. An illusion. And it works very well. I have plenty of relatives who believe every time they buy a Starbucks latte, they’re somehow helping African children. Brave souls.

It’s no wonder we resort to irony. We have to protect ourselves from sounding stupid or being humiliatingly mistaken in a very public venue. You can’t be mocked if you’re already mocking yourself.

We say, “I care!” Then we glance at the audience of the internet and say, “Unless you don’t care. Or this is something stupid to care about. Or if you have evidence that proves I shouldn’t care about it. Y’know what? Never mind.”

But irony is our own worst enemy. It’s too safe. It’s like dispelling our own magick before it pulls on its first heartstring. Advertisers and politicians are immune to this feeling of vulnerability. They have entire departments to fire if it doesn’t work out. So they continue to blaze on and gobble up all of the attention.

It’s no wonder we’ve become such ineffective magicians.

A DISEASE OF LANGUAGE

So let’s say hashtags are dead. Let’s say the U’s department heads and my friend are right and that hashtags are for idiots and worthy of nothing more than an eye roll.

How often do you click on hashtags to see who else is hashtagging about that topic? Do you ever hashtag your own posts so people will be able to find it more easily, thinking oh what a good librarian am I?

Maybe the death of the hashtag wouldn’t be a huge loss.

But there’s definitely something to be learned from the rise and fall of the little eight-pointed wand. People with lots of money profited off of a communications tool while we became embarrassed with it, ensuring that all of our favorite shows would be canceled and our least favorite politicians would poll well and show up everywhere we turned.

Why?

I can’t answer this question, because I’m only one person, but let’s ask ourselves . . . why? Why did we become so embarrassed with something so efficient?

The answer will be important because whether or not the hashtag is dead, something else is coming. Another communication tool. And it will involve words, which irrevocably involves magic.

This is where the disease of language comes back in.

I don’t want to tell you to use more hashtags. I just want to encourage everyone, especially myself, to learn how to see through things. To see through hashtag advertisements, through well-meaning hashtag activism that doesn’t actually do anything. To see what’s behind the language. What is the intent? What is the value? What is a hashtag campaign really trying to accomplish? What are you really trying to accomplish?

It’s our responsibility to become so searingly good with language, to have such clear intent and focus, that the irony melts away.

No matter what happens from this point forward, no matter how much noise is out there, no matter how helpless things seem, we still have to work. We have to be better with language and communication tools than corporations with millions of dollars to throw at it.

And if you ever feel really overwhelmed by the noise and that you can’t conjure the spells that will effect change, to tug on the right heartstrings in the right direction, I encourage you to take a drive down to Provo and read the terrible billboards along I-15. I’m sure you’ll gain some confidence.

Thank you.