I was recently asked to speak at the Writers and Illustrators for Young Readers conference in Sandy, Utah. It is, without a doubt, one of the best children's writers workshops in the WORLD.

I did my best not to sully the name too much.

Here's the speech:

Pajama Party in the Labyrinth

Writing Authentic Feeling from the Comfort of Your Own Home

I.

On Fear

Let’s admit that we’re all terrified.

Though we may experience brief flutters of steadiness—we feel good about a chapter, the right person compliments our work, an agent or editor asks to read our stuff—we’re still bonkers, out of our minds terrified. You guys invested money to come to this workshop and bare your souls on paper. You’re putting a lot on the line. It must be scary.

I’m here to tell you: that’s fantastic. Being scared is such a valuable, underrated experience. Only people who are scared can be brave, and bravery is arguably the most important aspect of our work. I believe the people who are most terrified are going to write the best stories. When you’re scared, you spark your survival instincts, and this resonates with every other human on the planet, regardless of their positions in life.

Of course, I don’t need to tell you this. You’ll be terrified no matter what I say, or how well you do in the publishing industry. So look forward to that.

II.

On Honesty

I believe there’s a way you can use this terror for good.

There’s a trick in acting. And that is not to act. An audience can smell an actor who’s “acting” because their emotions come across as flat or painted on. It’s like they’re trying to convince you that they’re “sad.” Or “happy.” Or “really enjoying this sex scene.”

So some actors—the best actors in my opinion—are honest about their current emotional state no matter the context of the scene. They channel however they’re feeling into their words. If they feel vomity during that love scene, they don’t try to hide it. If they feel pissed off during a magical moment, they play through it, and it works. It works because it feels genuine to the audience. And it reminds us that sometimes we feel vomity when we’re supposed to feel wonderful and maybe a little giddy when we’re supposed to feel morose.

Just admitting how you’re feeling in a moment can work wonders. Lying to yourself requires an incredible amount of energy. It’s better to be honest about where you are in that moment. Especially when writing. Instead of putting on the emotion the audience expects of you, you are allowed to let your genuine emotion seep out. It’s hard enough trying to pretend you’re happy going into the office or waking up in the night for a sick kid or letting someone important read your pages for the first time . . .

Why not let yourself off the hook when writing?

Now, as writers, we’re obviously in a much different position than actors. We don’t have costumers dressing us in lavish outfits or people writing our words for us. However, like actors, we do have to step onto a stage of sorts. We have to show up to the keyboard no matter how we’re feeling. And if we’re very lucky, lots and lots of people will see what we’ve done. In this sense, we can borrow that incredibly valuable piece of advice from actors: we can feel exactly how we feel.

I’m sure you’ve all read those words that lie limp on the page—those sentences where you can tell a writer was trying to feel a certain emotion that just wasn’t coming across.

‘When he kissed her, her heart swelled like the throat of a bullfrog and her skin tingled like Rice Krispies.’

As readers, we don’t appreciate feeling lied to. All stories are lies, but the best ones use truths as building blocks.

III.

Channeling Your Fear

This fear we all have squirming inside us can come in handy in a specific instance when it comes to writing. And that is getting started. On a novel. On the next chapter. On that slippery ending.

Raise of hands—how many of you have been terrified of the blank page?

Congratulations. You’re writers.

Now, if you’re anything like me, you may have tried to convince yourself that your job as a writer is to overcome that fear. That you’re meant to squelch your natural feelings in order to force yourself to write. But remember that valuable tactic actors use. If you’re being dishonest with yourself, then the words on the page can sound as if they’re delivered through a strained smile:

“I’m so happy I’m writing. What an easy, wonderful thing to do. I’m like J.K. Rowling. I’m Neil Gaiman. Ha ha ha! Yaaaaaay!”

Or with a false sense of confidence:

“She breezily sauntered into Crackbone Cave with gusto. “Caves?” she said. “I eat caves for breakfast.”

Or something. That sounded homoerotic. You get what I’m saying.

Instead of fighting your fear of writing, try channeling it. By being honest about your terror, you’ll share a lot in common with your main character. If there’s a lot at stake in your story, as well there should be, your characters are going to feel uncertain and afraid and vomity and helpless . . . just like you.

In his exploration of the Hero’s Journey, Joseph Campbell discusses the protagonist’s desire to turn down the quest. Consider how well this mirrors the writer’s life:

Your character is too afraid to respond to the call for adventure.

You feel like a fraud when you write.

Your character has more important things to do with her life.

Your partner just dropped a bottle of pills in the bathroom and your cat might have eaten one.

Your character doesn’t think she has the tools necessary to take on the journey.

You are sitting in your living room in your pajamas, trying to go on an adventure you do not feel ready for.

What better way to make your character authentic than to have them channel your fear, your joys, your hesitancy, your body’s desire to outright not want to go? Odds are the analogies this inspires will be a lot less terrible than those of an author who’s trying to convey a feeling.

Of course, eventually you’ll write through this fear, and on a handful of happy writing days, you’ll feel great. The blank page will seem like a playground of endless opportunity. In those moments, go and write the scenes where your character is feeling confident. Or, more interestingly, have them feel overconfident in a moment when that’s really not a good idea.

You, the writer, will say, “Why, good morning labyrinth. Oooooh. Aren’t we looking intimidating today?” And then you’ll skip down the first path you see and get a spike through the throat.

It is moments like these that make millions tune in to Game of Thrones.

In short, embrace your fear.

IV.

Enter the Labyrinth

That was the most important thing I had to tell you today, but I have a few pointers that might help you throughout the writing process itself.

The labyrinth of story winds before you, twisted, kinked, unknowable.

The floor is squishy and damp.

In the distance, something grunts and scrapes.

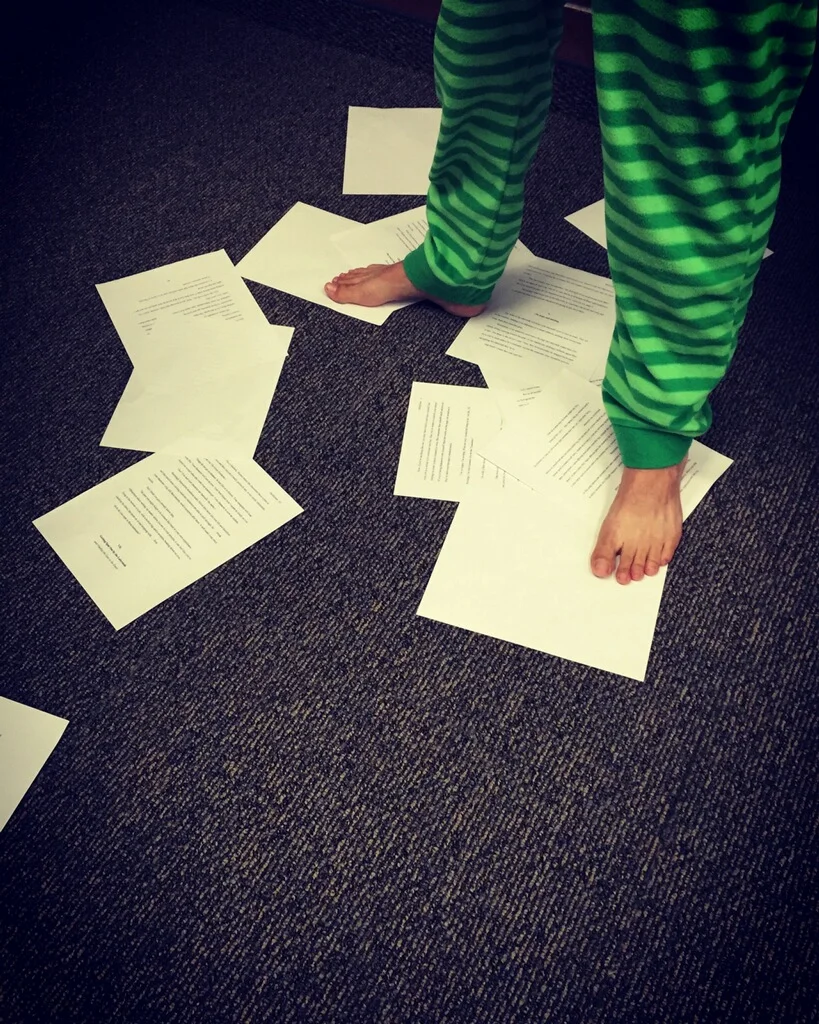

The wind is sharp, the stones breathe cold, and the moon is laughing at you in your pajamas.

You’re at home, wearing your pajamas, trying to embark on a journey that’s terrifying and exciting, and you feel like you don’t have the right tools on you. Hell, you don’t even have pockets.

If you’re like other writers, you’re going to dawdle. You’re going to wander outside the border labyrinth, occasionally peeking through the wrought iron gates, not really getting to the story because it’s complicated and scary in there. In order to buy yourself time, you’ll write some exposition. Maybe your character will see himself in a puddle and think, “He was a middle-aged man, beardy, with hazel coffee eyes, an overconfident gait, and who resembled Stanley Kubrick just as he was starting to swell.”

Remember, the story doesn’t actually start until your character steps through the labyrinth door (or is forced by gale, grunt or gunpoint). Until that moment they’re wandering around outside like idiots (just like we all do whenever we avoid writing). So toss out that exposition and description and just get your character into the labyrinth as soon as possible. Trust that the necessary bits will explain themselves once they are most needed.

This isn’t always easy to remember. The first draft of my most recent book that I sent to my agent (I won’t say who he is, only that he is strikingly brilliant and handsome), the story started on page 80. He negotiated me down to, I kid you not, page 7.

The readers want to get lost in the labyrinth, to experience the twists and turns and to wonder just how in the hell the characters are going to get out of there.

V.

On maps and plotting

The walls of the labyrinth will keep your character more or less on track. They act as the crucible, binding your characters to a single purpose, guiding them toward and away from their intended goal.

Remember, your characters must move through this labyrinth under their own steam, always striving toward the goal. As my handsome, strikingly brilliant agent likes to say, “Put them in the driver’s seat.” Sure, they’ll occasionally be dragged backwards by a vine or held captive by a minotaur, but for the most part, they should be actively navigating this labyrinth they’re in.

That doesn’t mean they can’t get lost.

These moments, of course, are when the fear will really start to creep in. Which direction will you go in this story? How do you know it’s the right way? How do you get to the goal? Sure, you can write an outline, just as your character can draw herself a little map of what she believes is the shape of the labyrinth. But keep in mind, you both might need to throw away your sketches and outlines at any moment. Because there’s your idea of the story. And then there’s the story itself.

Labyrinths do not like to be predictable. Your readers do not want to figure it out at a single glance. I know this sounds backwards, but the more plotting you do, the more likely your reader will be able to see the structure. If the labyrinth were easily malleable, bending to the author’s every whim, then it would become as predictable as our thought patterns, and it might as well be a maze in a Highlights magazine, and even children quickly tire of those.

You might say, okay, right turn, left turn, another left turn, straight ahead. But when you walk it, you will find the story doesn’t allow for that. The labyrinth has a mind of its own with shifting walls and hidden creatures, and unless you are a formulaic writer like Dan Brown or Danielle Steele, this is a really good thing.

If you’re doing it right, you will feel nearly as lost as your characters do.

Writing above all should be an exploration. You are spelunking into the depths of what you think. Of how the world works. Of what moves humans to act. If you write the first thing that comes to your mind, you’ll likely be writing someone else’s words that have wormed their way into your head.

So, stay uncomfortable, stay scared, and learn to love not knowing what’s around that next corner. Honestly, the less prepared you and your character are, the better. We, the readers, will feel the uncertainty in our teeth, and we will be hooked.

VI.

Navigating the Labyrinth

On Cheating, Super Powers and Dead Ends

First, cheating. If a wall miraculously crumbles, getting your character closer to the goal, that’s cheating. If a wall crumbles onto your character and breaks their leg so they can’t go on . . . that’s interesting.

Next, special powers. If your character has a super power of sorts, make sure it has a cost. Let’s say my character can walk through walls. Any time I want to. Great. There’s only one problem. My pajamas cannot pass through walls. I could easily walk through this dead end, but then I’d have to be naked. I may get a chance to peek ahead, but I’m going to need to get back into my PJs quick before my butt gets gored, or worse, admired by the minotaur.

Now, dead ends. Let’s say your character falls down a pit. Or they’re cornered by a giant scorpion. Or they break a leg . . . Let’s say all three.

You, the author, have no idea what to do next.

Congratulations. This is fantastic. Stories where the characters have a plan to escape a tight situation and then execute it nearly perfectly are, in my mind, intolerable. (I’m looking at you The Force Awakens.)

Things do not go as planned. In real life or in fiction. Your computer will lose your file. Your character will lose an arm. Your best friend won’t squee as loudly as you hoped she would when she reads your manuscript. Your character is now an orphan.

(See? You and your character are basically the same.)

Seemingly impossible situations make fiction feel more like real life and therefore are that much more exciting when the characters are able to pull through. So . . . break your character’s leg, kill their parents, send a scorpion after them. It will make your story crackle.

But I think you guys already know that.

The part you might forget is to connect this back to your own experience. Oftentimes when writing, no matter where you are in your process, it can feel like you’re lying at the bottom of a pit, with a broken leg, and a scorpion bearing down on you, clacking its claws, the point on its tail dripping with . . . lava.

How do you cope in these moments?

VII.

When the Labyrinth Spits You Out

Unlike our characters, authors can take a break from the labyrinth and find a small solace in the real world.

Things can get pretty dark. In your heart. In the labyrinth. In the futility of trying to bring worlds to life in another person’s mind. And that’s okay. You’re trying.

But I do have a recommendation when you’re feeling particularly miserable. A cure-all panacea that always helps me when I’m feeling down. And that is to read about the miserable experiences of authors you admire. Look at how long it took them to get where they are. Read George R. R. Martin’s old short stories. Watch the video of J.K. Rowling discussing the lean decade she spent trying to get the first Harry Potter book published, being turned down by countless editors. Watch that one on repeat. Watch Andrew Stanton “master storyteller” give a TED talk where he boils all of the most vital storytelling elements down to their essence . . . and then realize the movie he’s pitching is John Carter.

Moby Dick sold sixteen copies before Herman Melville died. Sixteen. Who knows? Maybe lots and lots of people will read your work after you’re dead.

Does everyone feel better? Great. Neither do I. BACK INTO THE LABYRINTH!

VIII.

On Endings

Toward the end of your story, right around the climax, your character should be feeling pretty desperate. They must think their way out of an impossible situation using a story device that the reader may not have considered. Otherwise the readers will be yawning their way through your formulaic structure.

So why don’t you try an act of desperation when writing your ending? What makes you feel like you’re going out on a limb? What scares you? What is something you’ve thought about that made you say, ‘No. I can’t write about that. Everyone will hate me. My parents will disown me. My editors will put my picture up on a wall with a sign that says DO NOT PUBLISH. I’m sure there’s a wall like that.’

I want to tell you to write that. Your readers will tell you if it’s working or not with genuine enthusiasm or strained smiles or by never emailing you back. Believe me when I say that no matter what your ending is, your editor will try to stuff it into a commercialized box. So you may as well go way out there with your idea, be as bold as you possibly can—kick down walls, set them aflame, kiss the minotaur—just so you have some negotiating space when your editor tells you you’re crazy.

I mean, hell, why not sing your ending? Ahem . . . I . . . am not going to do that.

Once again, I want to bring it back to fear. If you aren’t still scared in the end. If you feel perfectly satisfied, or if, heaven forbid, you’re bored, then it’s time to start knocking walls down. If the problem was solved too easily. Sometimes maybe you need to burn this labyrinth to the ground.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. How could you? You worked so hard on this. As a person who has thrown away four manuscripts and started over from scratch, some as recently as three months ago, I know the feeling. But ask yourself this. What if you throw away a Go Set a Watchman and write a To Kill a Mockingbird instead? That’s exactly what Harper Lee did. (Greedier hands dug her MS out of the trash—where it belonged.)

In the end, take comfort in the fact that your book will never be perfect. That this is all an adventure. That you’re in an impossible position and probably will remain there for the rest of your career. It’s super cool. Don’t believe me? Ask the most successful writer you know if they believe they’ve ‘made it’. See what they say.

We’re all lost in the labyrinth. We’re lost together. And the fact that it’s so terrifying is what makes us such great writers.

Thank you.

Photo credit: Alicia Van Noy Call