I was given the honor of speaking to the children's librarians of Utah last week at ULA.

This is how it went:

I love being wrong about books.

I should clarify: I like having my low expectations eviscerated by a book.

When I was sixteen, I fought learning with every fiber of my being. My desires in life were simple: I wanted people to laugh at my jokes and pretty girls to kiss me and to eat Fruity Pebbles with key lime pie yogurt instead of milk for three meals a day. Of course, in order to be around peers and pretty girls and in order to earn enough money to buy horrific sugar combinations that will ultimately destroy your colon and make you gluten- and dairy-intolerant, you need to stay in school. Or that’s what they convince you to believe anyway. So I set about becoming very good at doing the least amount of work I could possibly get away with.

Unfortunately for sixteen-year-old me, my mom was kind enough to scrape together funds on a flight attendant’s salary to send me to a private school where they don’t let you get away with minimal effort. My English teacher, Mr. Van Arsdell, saw right through my charming social butterfly façade and threatened to fail me if I didn’t get my act together. When he assigned As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner, I, fearing expulsion and loss of peers and pretty girls, forced myself to read the book in order to absorb any quizzable information.

I remember that painful anticipation of starting the dreaded “classic.” To sit down and read a three hundred page literary book felt like hoisting a boulder above my head and shakily holding it there for as long as it took to flip through the pages and skim over the words. If my eyes glazed over, if my attention wavered whatsoever, then the boulder would come crashing down, cave in my skull, and I would fail, thus ending my social life.

Just looking at As I Lay Dying’s sepia-toned cover, my sixteen-year-old brain knew precisely what I was in for. Some dusty old man would be lying in a dusty bed dustily recounting a life that probably involved a war and unrequited love and, y’know, hardship. It would be told in flowery language and thorned with SAT vocabulary that was too tangled for my one-liner, Fruity Pebble sensibilities. It would take me at least three weeks to read, and every page would be excruciating.

I wasted no time in getting this over and done with. I sat down, set the book in my lap, and promptly watched four hours of syndicated Friends episodes. In a series of zany, unforeseen events, Chandler and Joey won Monica and Rachel’s apartment in a bet and transformed it into a guy’s den, reigning supreme there for several episodes until the women agreed to let the guys watch them kiss for one minute in exchange for having their apartment back. How could anything compete with this? Even though I could quote each episode by heart, it was still far more appealing than the thought of hefting that boulder over my head.

Once there were no more episodes of Friends to watch (and thank goodness I didn’t live in the era of Netflix or else I’d have been doomed), it was time to begin As I Lay Dying. I winced, I took a deep breath, I opened the cover… and I read the book in a single sitting. Forget hoisting a boulder. Reading Faulkner’s prose felt as easy as falling. Or drinking water. This was not what I’d been expecting. Not the story. Not the simple language. Not the makeshift cast for a broken leg made out of a bucket filled with un-lubricated concrete that would end up peeling the brother’s skin right off of his calf muscle. None of it.

When I was finished, I even went back and reread one of the chapters six or seven times. Granted, this chapter was only one sentence long: ‘My mother is a fish.’ To my sixteen-year-old mind, this was a puzzle. When I first read it, I couldn’t understand what I was looking at. My mother is a fish. Was this a joke? A light moment to break up the otherwise heavy material? Had the book suddenly transformed into a fantasy story? My brain had no muscle for these things, and I honestly couldn’t figure it out. But the sentence’s sparse ridiculousness invited me to reread it over and over again. And I slowly pieced it together.

The mother was dying. Her lungs were filling with fluid. She couldn’t catch her breath. And to her four-year-old, the POV of this chapter, she looked just like a fish, pale and gasping, like her soul had flopped onto the shore of life and was starting to accept the fact that she probably was not going to make it back into the ocean.

In that moment my consciousness was ripped right out of my Fruity Pebble-fed sixteen-year-old body, and I found myself staring at this dying woman through a four-year-old’s eyes . . . My mother is a fish. This sentence captured what it’s like to watch your mother die and not understand what’s happening.

So this was what all the fuss was about. Faulkner. Somehow, impossibly, the prospect of watching Jennifer Aniston and Courtney Cox make out had lost some of its luster.

After this, I started cracking open other books to see where else I’d been wrong. It turns out I was wrong a lot. I became a bit of a literary snob: Salinger, Morrison, Steinbeck, Shelley (Mary Shelley, that is). When Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone came out, I snorted. In derision. As one does when one believes one is above these sorts of things. I was a literary man now. And then a girl I had a huge crush on asked if I wanted to read the first book together before the movie came out. Yes, I said, believing I was agreeing to something else entirely. We read it out loud, Rowling constructing relationships that felt like a crackling hearth to warm our hearts beside, using dialect that tickled accents into our throats, and building mysteries we had no idea we were meant to solve. My crush and I actually finished whole chapters before making out.

After this, I became obsessed with reading anything and everything within reach. Except comics. Comic books were embarrassing, flimsy things, filled with improbable rebirths and fights in tights and only supported by emotionally stunted adults. Comics didn’t constitute real reading.

And then I stumbled across Blankets by Craig Thompson, which from the outside looked enough like a real book that I wasn’t embarrassed to read it in a Borders café (and save the $35, which would have broken my college budget of zero). And I became too lost in the story to care about crying in public when I read the scene where a Christian teenager reads a handwritten letter from a girl and pleasures himself for the first time based not on a picture but on the shape of her words and imagining how much pressure her fingers applied with the pen. And I realized that I had somehow convinced myself, as many adults have, of the ridiculous notion that words are worth less if there’s a drawing next to them. It didn’t take long for me to discover that I was wrong about a lot of the tights and fights comics, as well.

I’m not sure when it happened exactly, but at one point in the last couple decades I decided every book under the sun was worth giving a fair shake. Particularly the ones for which my brain generated preconceived notions.

And now I regularly experience that feeling of being delightfully wrong. Books that I was certain would trickle through my eyes and out my ears like vapor have defied all expectations: El Deafo, Gone with the Wind, The Book with No Pictures, Stiff, Anna Karenina, I Want My Hat Back, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Batman’s Mad Love, Eating Animals, Beloved, Captain Underpants, Filmish, American Elf, The Remains of the Day, A Remembrance of Things Past, A Walk in the Woods, The Buddha manga, Pastoralia, The Poisonwood Bible, Me…Jane, Mere Christianity, Swamp Thing, Smile, Sisters, The Goose Girl... I could go on and on. (I’m really hoping Twilight doesn’t disappoint when I finally get around to it.)

So that was my journey. From a kid who fought learning with every scrap of his being to someone who reads well over a hundred pages a day. Now I’m on the other side of it. With you guys. And instead of giving literature a shot, I’m tasked with getting others to give literature a shot. (It’s hilarious to me that I thought high school was difficult.)

So based on my experience as a non-reader who equated tackling a classic with hefting a boulder above his own head, I have come up with a thesis statement. This can be helpful when trying to figure out how to solve a problem. It’s like casting a spell. You have to have very specific parameters.

Here it is: I believe that what stands between any person and great, life-shaping literature is a matter of expectation. Our eyes take in a book’s cover and its title, maybe we read a review or hear a friend’s take, our brains sum up the plot, and we anticipate boredom. Or hatred. Or difficulty. Or triggers. Or problematic views. And we don’t pick it up. And we stay in our comfort zones. And we are convinced that what we like is perfect and what others like is garbage and we remain utterly surprised that other people do not think or vote or empathize the way we do.

I am all about destroying book bias, whether it’s for classics or nauseatingly popular titles. Obviously, classics need a bit more help. Which is unfortunate because they are the ones that get us to ask the most interesting questions.

As you know, getting teens to read presents a unique problem. Unlike my mom, I can’t scrape together my writer’s salary and send every kid to a private school where teachers will watch them like hawks as they delve into interesting or challenging material. Our magic has to be much more clever and far-reaching. I hope you are as delighted by this problem as I am.

I’m going to give you two quotes that have been playing tug-of-war with my thoughts over the last couple years. Even though they are saying near opposite things, I wholeheartedly agree with both of them.

The first is from Neil Gaiman:

“Well-meaning adults can easily destroy a child's love of reading. Stop them reading what they enjoy or give them worthy-but-dull books that you like – the 21st-century equivalents of Victorian 'improving' literature – you'll wind up with a generation convinced that reading is uncool and, worse, unpleasant.”

The second quote is from Alan Moore:

“It’s not the job of the artist to give the audience what the audience wants. If the audience knew what they needed, then they wouldn’t be the audience. They would be the artists. It is the job of artists to give the audience what they need.”

You can see the problem. One advocates for letting readers choose whatever strikes their fancy. The other prescribes strapping them down and pouring much-needed molten information down their gullets.

Now, both of these quotes are generally directed toward specific ages. Gaiman is talking about kids and telling parents to rest easy when their child refuses to read anything beyond Diary of a Wimpy Kid (which is great) or the instruction booklet for Minecraft (which I have not read). These kids’ tastes are just forming, after all. If you allow them to carve their own path through literature, it’s more likely to feel like an adventure to them and they may just, with a little luck, become readers for life.

Moore is talking to grown-ass adults about grown-ass adults, comic book readers mostly, who have a propensity for reading stories containing those dreaded tights and fights. He’s encouraging the writers of comics to throw out the three-act structure and plots based around whose super power can overcome whose and to replace it all with gritty social commentary, gussied up in yellow, cyan, magenta, and black to make the more difficult messages simultaneously ironic and easier on the eye.

I write for teens. You work with teens. And they’re nestled right in between these two quotes—their excitement about literature fragile and their propensity to tackle challenging material tenuous. And who can blame them? The prospect of seeing Rachel and Monica make out is a drop in the ocean of the intrigues available today.

If we push too hard, teens may abandon books for a dopamine-gushing electronic world that never ceases to satisfy—if only on a surface level. If we let them read whatever they want, they may never challenge themselves to venture outside their comfort zones, and their brains will be caught in a creaky hamster wheel of stagnation and manga.

But these are surface efforts. You and I must venture deeper.

So how do we delicately guide reluctant readers toward crackling literature that will awaken empathy and allow their brains to fill in the spaces between the words and to slowly realize as Gaiman puts it, that everyone else is another me?

Well, it depends on which part of the factory line you’re on, doesn’t it? My job is different than an editor’s job, which is different than a cover designer’s job, which is different than your job as librarians. Some of our solutions are quite simple when addressing the problem of competing with attention-grabbing apps and technologies. I have been told to make my chapters shorter because teens like short chapters. Editors have started making titles shorter and more attention grabbing while some advertisers have even gone so far as to pepper swear words into the titles so they scream for attention. Cover designers have the slightly more difficult job of catching the eye without talking down to teens.

Here’s what this process is like from one author’s perspective.

On the one hand, I want to create readers for life, to write something as sticky as the greatest bestsellers so that if a reader picks up my book, real life will melt around them, until the chapter or better yet the entire book is finished. I want my work to act as kindling that will light a fire in their eyes that will burn through the library stacks—a furnace that can only be fed by ink and new ideas. On the other hand, I don’t want to write fluff. I want the material to be new and challenging, and I want to knock down walls in their lives.

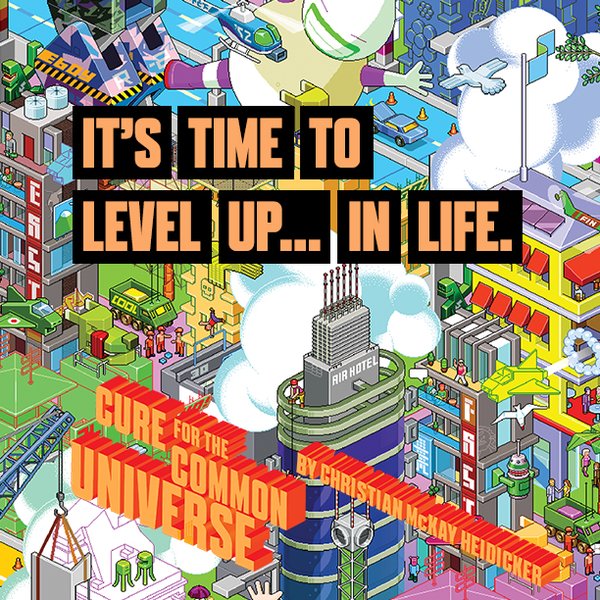

(This is the part of the talk where I discuss my book. Don’t worry. I’m as allergic to self-promotion as you are sick of hearing it. It just feels relevant.)

My first effort in YA, Cure for the Common Universe, is about a kid who’s committed to video game rehab ten minutes after he gets the first date of his life. Fortunately for him, “V-hab” is a gamified recovery center where patients (or “players”) can earn points by learning real life skills like playing the ukulele or cooking a tofu scramble or winning a Four Square tournament. The main character, Jaxon, is trying to earn one million points in four days so he can be released and make it back to his date, which he thinks (operative word) will cure him of his gaming addiction.

Most people who hear this synopsis or read the book think I’m a gamer. A hardcore gamer at that. And I’m not. I don’t even own a console and didn’t when I sold the book. The truth is much less romantic. After failing to sell three other books, I sent a list of story ideas to my agent, John Cusick, including this one about a rehab for video game addicts, and he chose the one that was most commercially viable—the one that just might get gamers to look away from the screen and pick up a book.

I approached a book about video game addiction from an anthropological perspective, locking myself in my room for months with game consoles of all kinds and trying to get myself addicted. After my eyes began to glow a pale blue and I had ones and zeroes pumping through my bloodstream, I went cold turkey on caffeine and sugar and alcohol and all electronics (including my computer and phone)—and for a solid month committed myself to a recovery center of my own making, learning the play the ukulele and becoming slightly better at Four Square in order to write the book.

The writing was hugely rewarding. It allowed me to explore all of the itchy tendencies I had as a sixteen-year-old when I wanted everything to taste sweet and to have all good things fall into my lap with minimal effort. I recharted the course I’d taken as a teenager when I learned that life doesn’t operate like a video game. After high school, there’s nothing in life as straightforward as There! Dragon! Kill! and women were not waiting for me to flirt with them as they seemed to be in Friends.

Despite its deeper questions about desire and addiction and how we all seek to cure our loneliness, I tried to write something a younger me would have found delightful and easy to read. I tried to make the prose simple and electric with lots of white space and jokes and Easter eggs hidden throughout. I read the book out loud over and over again until I had that feeling that the reading was as easy as falling. Maybe even as easy as guiding a joystick.

I enjoyed writing Cure—it turned parts of me inside out—but if I’m being honest, it was born of a formula: I pitched a plot with a hook, an agent selected it, and it sold. Was approaching a book this way a smashing success? I have no idea. It’s actually much more difficult for authors to tell if we’ve done our jobs well or not. I do have one story to share with you though. (B&N story)

Here’s the thing. It isn’t my job to get good books into kids’ hands. That would be creepy. Especially with this beard. It’s my job to create good stories, but when it comes to actually getting the kids to read, that is the job of schools, advertisers, booksellers, and of course, yours.

This is where my heart goes out to you, dear teen librarians. I can only imagine you earned degrees in library sciences to better lubricate the flow of ideas and information to the masses. Whether you became librarians for teens intentionally or you just stumbled into it like many people I know, you probably wouldn’t mind seeing more teen readers. And you probably wouldn’t mind seeing them read more challenging things—or at the very least dipping their toes in. And you don’t have the luxury of classrooms where you can force these kids to read the things you like.

As librarians, you can stoke a reader’s interests in a thousand ways, from creating engaging book displays to holding events like Elizabeth’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark during Halloween to filling the gaps between their burning interests, like video games, and reading contests, etc. I would actually love you to share some of those ideas with me.

You may be concerned that I’m about to tell you how to do your job. That I’ll suggest you gamify your library so kids earn points by reading books. But we all know kids can smell the intent beneath stuff like that. No, I’m only here to tell you about my approach to writing stories and to ask you about your approach and to point out where I think our current system is failing teens.

Classic has a dusty, crusty old feel to it. In cover design. In titles. In anticipation. And we don’t have the big five publishers dedicating their time and effort to gussying up older titles. Sure, they can update classics, slap a new coat of paint on it, pepper in some swears, cut down on the page count, and call them Saving Hamlet or Taming of the Drew or the Much Ado about Nothing manga, but it isn’t exactly Shakespeare, is it? Literally.

Here’s what I think is missing when it comes to classics on library or bookstore shelves: tantalizing spoilers.

Here’s a boring title: A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Even though I read a lot these days, that title still rankles the bored teenager inside me. “Oh, does a tree grow in Brooklyn? Does it really? Boy, I can’t wait to read about that. Tell me when they chop it down and turn it into a skate ramp.” But you can’t really rename this book ‘A mother addresses the upsides of one night stands with her daughter’ (an actual scene in that book) because it isn’t as catchy and it would probably result in more books burned, even though that would probably get a lot more people to read it.

I want to find what is in these books would snag a teen’s interest and get it outside of the book. What were the scenes in a text that nearly seared a hole straight through your heart? How do you put that front and center?

Here are some examples of books that have a very stale exterior and are absolutely exploding with life on the inside. See if you can tell me which books I’m talking about.

- To save her from slavery, a mother cuts open her baby’s throat and buries her, carving a name into a wooden headstone. Many years later, a full-grown woman shows up at her doorstep with a scar across her throat, claiming that same name.

- A girl’s mother puts down the nice picnic blanket before she cuts her own head off because even though she’s finished with this life and everything in it, she doesn’t want her family to have a big mess to clean up. Unfortunately for her sisters, she forgot that heads roll.

- It’s the 1860’s and a southern woman scolds a northern woman for returning to a black man using the ‘n’ word because they are only allowed to call each other that.

- Instructions on how to draw a realistic human anus and when that can come in handy.

- A girl whose father has punched her ears so many times they’ve turned cauliflowered, is convinced by a rat that the only way to become a princess is to kill the princess.

- In this book, you can tell who’s evil because their pupils are rectangular like that of a goat’s.

While trying to untangle this knot that binds teen readers, I called my agent, John Cusick, who is brilliant and lovely and thinks just as much about packaging and titling and sales as I do about writing. I started our conversation by fretting about some data that claimed that fifty percent of readers of young adult books were adults and I told him that to a writer this felt like being an engineer who designs baby change stations for men’s restrooms and discovering they’re being used to hold one old man’s dentures while he services a glory hole. It’s nice that the changing station is being used, but . . . that isn’t quite its intended purpose, is it?

John calmed me down by pointing out that this doesn’t mean that half of the sales of any YA book were to grown-ups. It means that so many adults decided to pick up Hunger Games and The Fault In Our Stars and Twilight that they seriously tipped the scales. So that’s nice to know. Teens are reading teen books.

John also, as is his wont, said something very wise, and he may have solved the entire problem in this speech. He pointed out that trying to decide what teens need or want without their input will always feel like proselytizing. And none of it will ever stick because we’re all going to have different book suggestions and we’re all going to wince at different stories. The same people who are offended by the reference to a threesome in Grasshopper Jungle may overlook the emotionally abusive relationship in Twilight.

We all know at the very leas that teens want to be treated like adults. They want to be part of the conversation, especially when it comes to their lives. And the marvelous thing about great literature is that it will never tell you what to do. Literature cannot tell a teen to have a particular type of sex or do a particular kind of drug or be a cog in systematic oppression. Great stories can only ask the consequences of these things. We are not in the business of pushing propaganda. We aren’t pushing rules. We’re pushing questions.

By turning the content of these books inside out we’re showing them that texts are alive things that structure conversations. We point out that no question is dangerous. And no question is stupid. Especially when you’re learning how the world operates. Some books ask more intricate questions than others, and that’s perfectly fine.

By giving teens the space and opportunity to screw up the answer to these vital questions as grandly as adults do, we may in fact discover that, like sixteen-year-old me, what they want and what they need end up being the exact same thing.