III.

“Amateurs borrow. Masters steal.”

--Picasso . . . or T.S. Eliot or John Lennon or actually, you know what, let’s just say Christian McKay Heidicker, I came up with this quote, I did

When I first heard that masters steal, I was certain it didn’t mean what I thought it meant. Stealing sounds like straight-up plagiarism, the sort of thing that will get a college student expelled or the first lady of the United States a daylong news cycle. And what did it mean to borrow something as an amateur? Would they stick an old idea in their book only to have the words vanish before the reader’s very eyes? Confusing.

It took a great deal of experimentation, screwing things up, getting things right on occasion, and reading a massive amount of books to truly understand what this quote meant. I’m hoping to save you some time and some eyestrain today by explaining it.

We are all amateurs in the beginning, timidly nibbling from great works. And we do this, I think, out of ignorance. The author mind can be lazy, and when we first start writing, we’re very much in danger of steering the story straight into a well-worn rut that audiences and editors have seen so many times they’ll throw up all over your pages out of sheer boredom. This, I believe, is what this quote, my quote, means when it says that amateurs borrow. We put things on the page because they feel familiar and we get a little squirt of dopamine that says, yes, you have come up with something original. Good job.

So, how do you steal like a master? And how do you not feel like a fraud while doing it? (I don’t need to tell anyone in this room that I am not a master, I am still figuring this stuff out, but here’s my thought process so far.)

Neil Gaiman got his fame as the prince of storytelling by writing the Sandman comics because nobody had ever seen anything like it before. When I was in high school, I dove into the series in awe at the sheer scope of the work. I remember being impressed with the massive cast of characters, especially the amount of detail given to the minor throwaways. In the realm of dream, outside of Morpheus’s castle, there is a shack tenanted by Cain and Abel. The brothers leant comic relief to the dreary scene every time wolfish Cain murdered bumbling Abel, only to have Abel spring right back to life again. As a high-schooler, I was blown away by this idea. Everybody was. How did this man manage to spin these incredible characters out of nothing?

The answer is, of course, he didn’t. He stole them. Now, before you rightly point out that of course Cain and Abel aren’t original characters, that the genius comes from turning the Biblical figures into comic relief, you should probably know something. I went on to read Swamp Thing by Alan Moore, which was written before Neil Gaiman had published his first comic. In Swamp Thing, Moore shows the gate to dreamland, guarded by, you guessed it, comically murderous Cain and poor, hapless Abel. It wasn’t until I read even further that I discovered these same comedic iterations had been the host of a collection of scary stories in the 1960s.

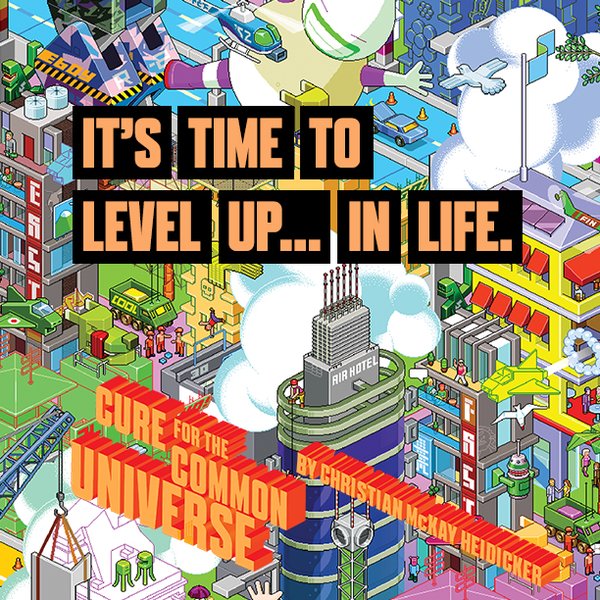

It turns out, nearly every one of Gaiman’s characters, including those from his children’s books and books for adults, are a direct parallel, from their name right on down to their narrative drive, of a figure in religion or myth or golden age comics. He just combined them in interesting ways, the way I accidentally injected a little Gone with the Wind into a contemporary book about a video game addict. The difference was, nobody had seen this sort of thing in a comic book before. Well, most hadn’t anyway. This is part of why I write for kids. I can break down new walls, and their little jaws will drop and their eyes bulge out. The pages in their books are still blank. And I seem like a genius.

If you steal, you’ll be in great company. Shakespeare stole, of course. Every play he ever wrote. So did Tolkien. And if you don’t know this, go read some history or Wagner’s Ring Cycle. You’ll be delighted and maybe a little appalled. Either way, we have to admit that even though we can locate the wellspring of these writers’ genius, it doesn’t diminish their accomplishments in the public consciousness. Gaiman and Moore and Tolkien and Shakespeare wrote fan fiction. (So did E.L. James for Fifty Shades of Gray, but let’s ignore that for the time being.) If this doesn’t encourage you to steal, I don’t know what will.

Once I recognized just how often my favorite writers lifted characters and locations and story arcs from other places, I went on a bit of a stealing spree. For Throw Your Arm Across Your Eyes and Scream, I stole King Kong and Anne Darrow, the damsel he kidnaps and carries to the top of the Empire State Building. I stole the Blob and the creature from the Black Lagoon and a chilling young pyromaniac with blond pigtails from a brilliant movie called The Bad Seed (which was based on a play, which was based on a book).

Of course, I didn’t check the availability of any of these characters, and Simon & Schuster’s legal team is looking into whether or not I can actually use them as I write this. This might sound unnerving, the idea that I could lose my characters with a single click of a lawyer’s pen, but it isn’t, actually. Worst-case scenario, I have to rename all of my monsters. King Kong will become Titan Ape, and the Creature from the Black Lagoon will become Fish Lips Cunningham. (If it’s actually an issue, I’ll spend a lot more time on those names, I promise.) Renaming familiar characters has been done before, after all. Watchmen, which I’m sure you’ve all heard of, was based on pre-existing superheroes. When DC comics ran into legal issues, Moore just changed their names and costumes. This works because people recognize models of superheroes. They recognize models of monsters and models of tragic historical figures and, when it comes to E.L. James stealing from Stephanie Meyer, they recognize models of abusive relationships.

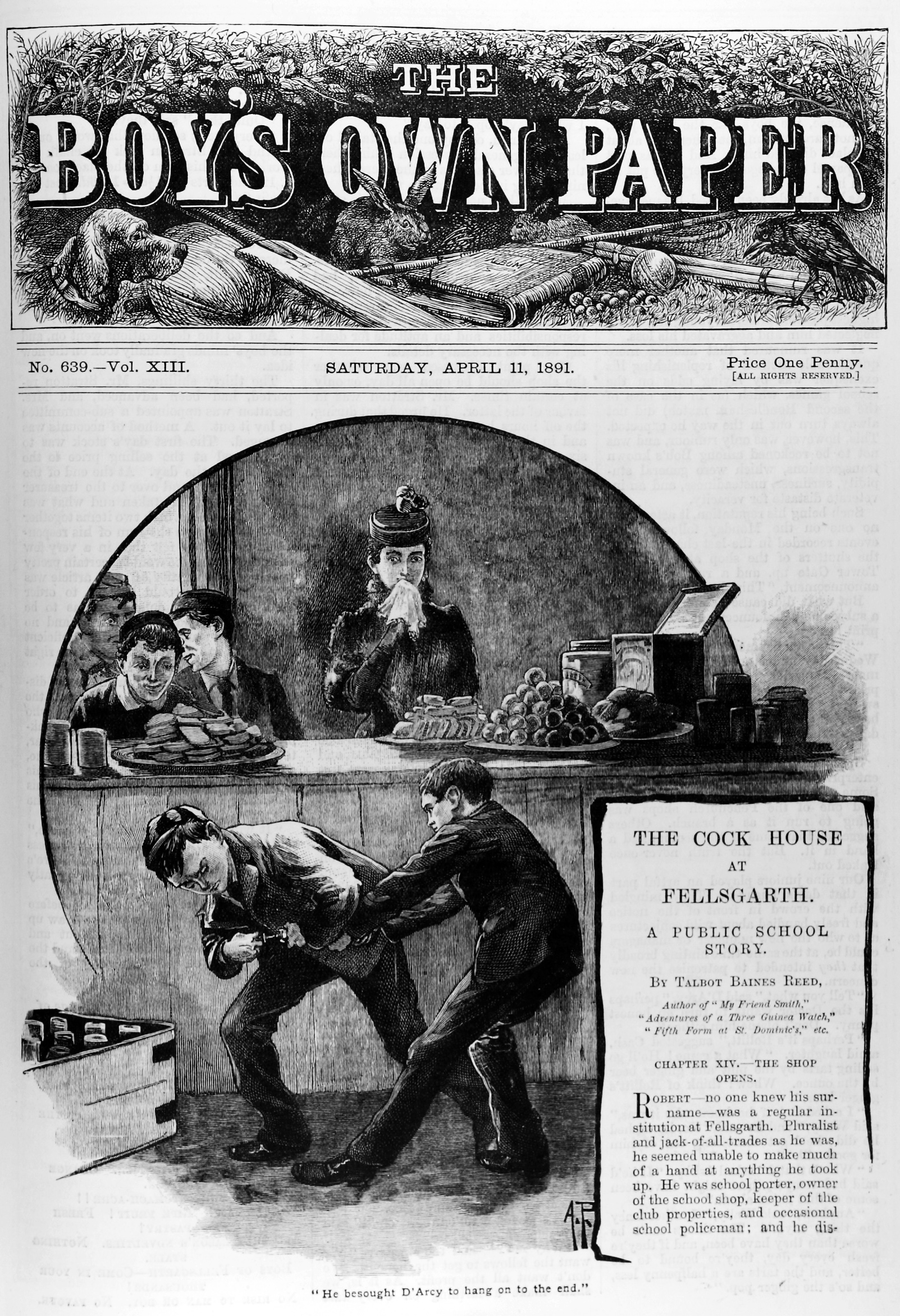

Now if you’re anything like me, you’re growing skeptical at this point. By looking at the toweringly brave works of today—Grasshopper Jungle and The Hate U Give and El Deafo—you’ll recognize that they look and feel nothing like the stories meant for kids a century ago or even a decade ago. And you’re right. They’re very different. So if we are in fact recreating the same stories over and over again, stealing characters from works already stirring in the public consciousness, then how is literature evolving?

It’s time for another quote.